Overview

To do Diagnosis of a Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaque, Doctors are constantly looking for better ways to identify these vulnerable or high risk plaques before they cause a serious event.

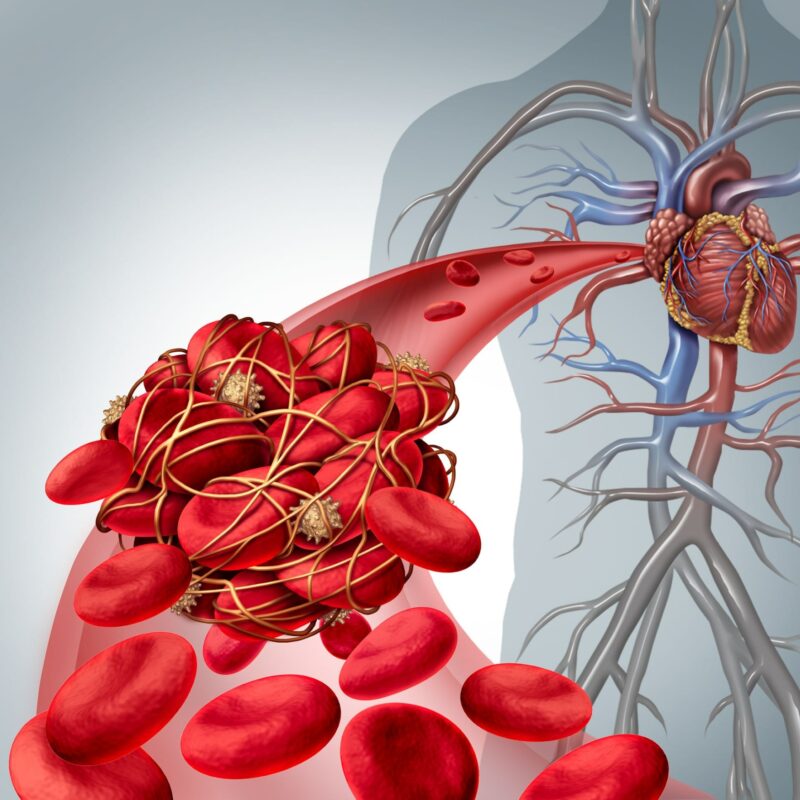

Atherosclerotic plaques are deposits of fatty substances and other materials that build up in your arteries, and some of these plaques are particularly dangerous because they are more likely to break open, or rupture. When a plaque ruptures, it can cause a blood clot to form, potentially leading to a heart attack (myocardial infarction, MI) or a stroke.

To do this, medical professionals use a variety of sophisticated tools, including both non invasive imaging (like special CT scans and MRI) and invasive techniques that look inside your arteries (like tiny ultrasound or light probes). These methods help them understand not just how much an artery is narrowed, but also the specific characteristics and composition of the plaque, which is key to determining if it’s vulnerable and could cause problems in the future.

In Details: What Doctors Do to Diagnose Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaques

Quick list of Diagnostic tools:

- Coronary CT Angiography (CCTA)

- Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) and Virtual Histology IVUS (VH-IVUS)

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

- Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS)

- Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) Imaging

- Nuclear Imaging (PET scans)

- Coronary Angiography (often with Fractional Flow Reserve, FFR)

Coronary CT Angiography (CCTA)

This is a non invasive imaging method where you lie in a scanner, and X rays are used to create detailed 3D pictures of your heart’s arteries. Doctors use CCTA to identify several features of plaques that suggest they might be vulnerable. These include positive remodeling, which is when the artery wall expands outwards to make space for the growing plaque, potentially hiding the true extent of the blockage.

They also look for low attenuation plaques, which appear darker on the scan and indicate a high fat content. Other important signs are spotty calcifications (small, scattered calcium deposits) and the napkin ring sign (a specific pattern with a low fat core surrounded by a brighter outer rim), both of which are strongly linked to high risk plaques.

CCTA is valuable because it can survey your entire coronary tree and can help predict the risk of future events, even from plaques that aren’t yet causing a major blockage.

Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) and Virtual Histology IVUS (VH-IVUS):

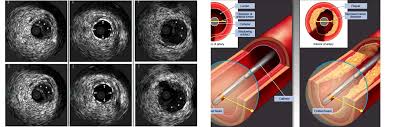

This is an invasive procedure where a very thin, flexible tube with a tiny ultrasound probe at its tip is guided into your coronary artery. Once inside, it sends out sound waves and creates detailed cross sectional images of the artery walls from the inside out. IVUS helps doctors measure the plaque burden (the amount of plaque occupying the artery wall) and how the vessel has changed shape.

Because standard IVUS has limitations in distinguishing all plaque components, advanced versions like Virtual Histology IVUS (VH-IVUS) process the ultrasound signals to create a color coded map of the plaque’s composition, showing different types of tissue like fibrous, fatty, and the necrotic core (a dangerous, lipid-rich center within the plaque).

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT):

This is another invasive imaging technique that uses near-infrared light to generate incredibly high resolution images, much finer than what IVUS can provide. OCT is especially good at directly measuring the fibrous cap thickness, which is the thin, protective layer covering the fatty core of the plaque. A fibrous cap that is very thin is a hallmark of a thin cap fibroatheroma, a highly vulnerable plaque.

OCT can also clearly show lipid rich cores (fatty deposits), signs of inflammation (like macrophage infiltration, where immune cells gather), cholesterol crystals, and small calcium deposits within the plaque, all contributing to a comprehensive assessment of its stability.

Near Infrared Spectroscopy:

Often used alongside IVUS, this invasive technique is specifically designed to measure the lipid content within plaques. Near Infrared Spectroscopy creates a chemogram which is essentially a chemical map that highlights areas rich in lipids.

Other Similar Questions

Can blood tests help identify vulnerable plaques?

Yes, certain blood tests can detect biomarkers (biological indicators) related to inflammation and plaque instability, such as C reactive protein (CRP) or specific enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). While useful for general cardiovascular risk assessment, their ability to pinpoint a specific rupture prone plaque is still being researched.

Is it always necessary to find a vulnerable plaque to assess my heart risk?

No, doctors also consider your overall cardiovascular risk factors, including age, smoking status, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels, as well as the total amount of plaque throughout your arteries. This comprehensive approach helps assess your vulnerable patient status, which is broader than just finding a single vulnerable plaque.

If a vulnerable plaque is found, does it always need immediate treatment?

Not necessarily. The presence of a vulnerable plaque doesn’t automatically mean it will rupture soon. Doctors will evaluate your individual health profile, other risk factors, and the specific characteristics of the plaque to determine the best course of action, which often involves lifestyle changes and medications aimed at stabilizing the plaque.

Area of Research:

- Further investigation is focused on the concept of the “vulnerable patient,” which considers overall disease activity and systemic factors in addition to specific plaque features. This aims to improve personalized treatment strategies and potentially target therapies more effectively.

Resources:

- Dawson, L. P., & Layland, J. (2022). High-Risk Coronary Plaque Features: A Narrative Review. Cardiology and Therapy, 11(3), 319–335.

- Gaba, P., Gersh, B. J., Muller, J., Narula, J., & Stone, G. W. (2022). Evolving concepts of the vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque and the vulnerable patient: implications for patient care and future research. Nature Reviews Cardiology.

- Hafiane, A. (2019). Vulnerable Plaque, Characteristics, Detection, and Potential Therapies. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 6(3), 26.

- Kurihara, O., Takano, M., Miyauchi, Y., Mizuno, K., & Shimizu, W. (2021). Vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque features: findings from coronary imaging. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology, 18(7), 577–584.

- Sakamoto, A., Cornelissen, A., Sato, Y., Mori, M., Kawakami, R., Kawai, K., Ghosh, S. K. B., Xu, W., Abebe, B. G., Dikongue, A., Kolodgie, F. D., Virmani, R., & Finn, A. V. (2022). Vulnerable Plaque in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: Identification, Importance, and Management. US Cardiology Review, 16, e01.

- Toutouzas, K., Benetos, G., Karanasos, A., Chatzizisis, Y. S., Giannopoulos, A. A., & Tousoulis, D. (2015). Vulnerable plaque imaging: updates on new pathobiological mechanisms. European Heart Journal, 36(47), 3326–3335.

- van Veelen, A., van der Sangen, N. M. R., Henriques, J. P. S., & Claessen, B. E. P. M. (2022). Identification and treatment of the vulnerable coronary plaque. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med., 23(1), 039.