Overview

Angina is often described as a tightness or pressure in the chest, jaw, or arm, that happens when your heart muscle isn’t getting enough oxygen-rich blood. This lack of oxygen is called myocardial ischemia. Understanding What Are the Causes of Angina helps in recognizing and managing this condition.

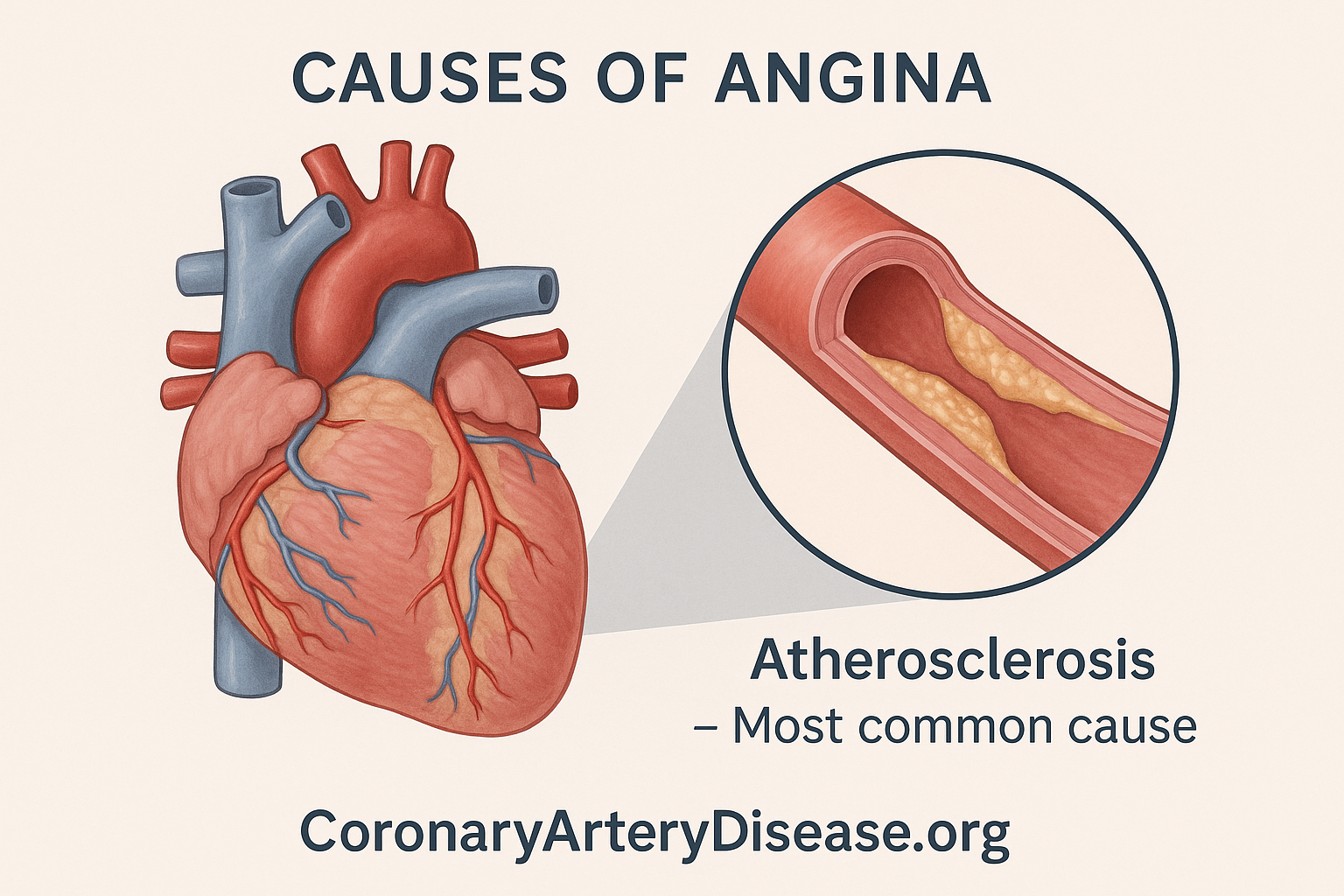

The most common cause of angina is a narrowing of the heart’s own blood vessels, known as the coronary arteries. However, there are also other, less common causes that can lead to your heart muscle not getting the blood supply it needs.

In Details

- Coronary Atherosclerosis (the most frequent cause).

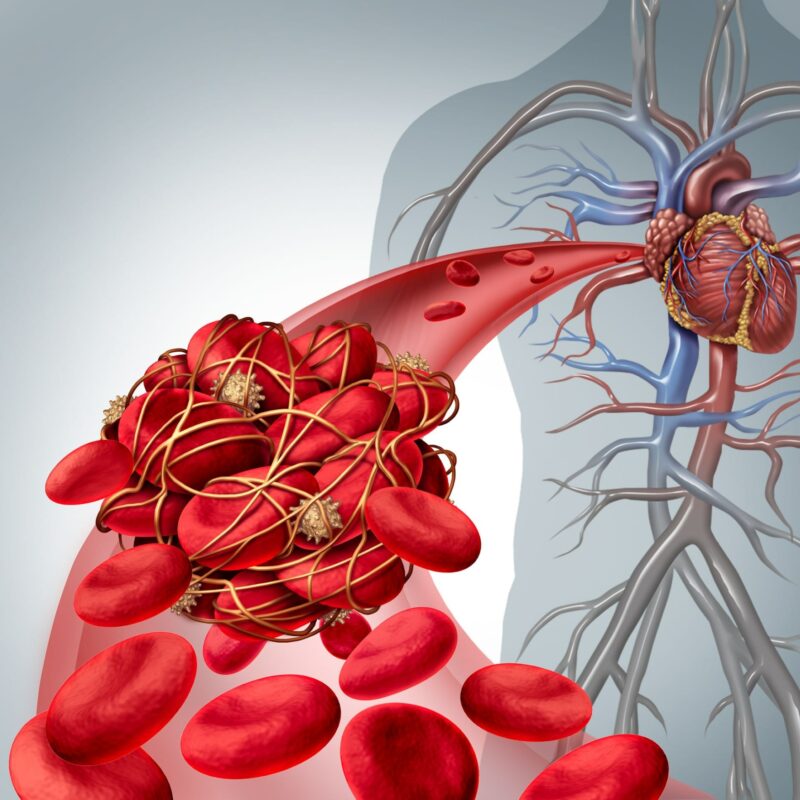

- Other Coronary Artery Diseases: These include blockages (emboli), sudden artery tightening (spasm), blood vessel inflammation (vasculitis), Kawasaki disease, and heart/vessel birth defects (congenital anomalies).

- Cardiac Diseases: Such as a thickened heart muscle (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), very high blood pressure (severe hypertension), or issues with a major heart valve (severe aortic valve disease).

- High Output States: Conditions where the body’s demand for blood is unusually high, like severe anemia (low red blood cell count) or an overactive thyroid gland (thyrotoxicosis).

The usual underlying problem causing this is coronary atherosclerosis. This is a common and progressive disease where plaques, which are fatty deposits, build up inside the walls of the coronary arteries. These arteries are crucial because they are responsible for supplying oxygen-rich blood directly to the heart muscle itself. As these plaques accumulate, they narrow the arteries, making it much harder for sufficient blood to reach the heart, especially when the heart has to work harder, such as during exercise, emotional stress, or exposure to cold temperatures.

It’s important to know that while coronary atherosclerosis is very common, its presence doesn’t always result in angina. However, when it does, it’s a clear sign that the narrowed arteries are struggling to meet the heart’s oxygen demands, leading to the characteristic discomfort of angina.

Beyond atherosclerosis, other, less common conditions can also lead to angina. These can involve other diseases that directly affect the coronary arteries themselves, such as emboli (small blood clots or other material that travel through the bloodstream and can block an artery), spasm (a sudden, temporary tightening of the artery walls that restricts blood flow), or vasculitis (inflammation of the blood vessels). Very rare conditions like Kawasaki disease (which primarily affects children and can cause inflammation of blood vessels) or congenital anomalies (structural problems with the heart or its blood vessels that are present from birth) can also be underlying causes.

Furthermore, angina can result from other heart conditions that put an excessive strain on the heart, even if the coronary arteries are not primarily narrowed by atherosclerosis. For instance, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a condition where the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick, making it harder for the heart to pump blood effectively and potentially leading to oxygen deprivation. Similarly, severe hypertension (very high blood pressure) and severe aortic valve disease (a problem with one of the heart’s major valves) can significantly increase the heart’s workload, causing it to demand more oxygen than it can receive, thereby triggering angina.

Lastly, conditions known as high output states can cause angina because they force the heart to work exceptionally hard to pump enough blood around the body. Examples include severe anemia, and thyrotoxicosis ( an overactive thyroid gland that speeds up the body’s metabolism and places a greater demand on the heart ).

Other similar questions

What is angina?

Angina pectoris is a clinical syndrome of discomfort, typically felt as a pressure, tightness, or discomfort in the chest, jaw, arm, or other areas, that occurs when your heart muscle isn’t getting enough oxygen-rich blood

Can you have coronary artery disease without experiencing angina?

Yes, absolutely. It is possible to have coronary atherosclerosis (fatty deposits in the arteries) without any symptoms of angina when having atherosclerotic plaques that don’t cause stenoses( narrowing of the coronary arteries ). Also, myocardial ischemia (lack of blood flow to the heart) can occur without pain, a condition known as ‘silent ischemia’ which is more common in elderly patients and those with diabetes mellitus.

Can other things cause chest pain that isn’t angina?

Yes, there are many other causes of chest pain that are not related to angina. These can include problems with your lungs (like pneumonia or pulmonary embolism), issues with your digestive system (like esophagitis or a peptic ulcer), or even problems with your chest wall (such as muscle strains or costochondritis). Sometimes, psychological factors can also contribute to chest pain. So, it’s very important to differentiate between cardiac angina and other non cardiac causes of chest pain.

Resources

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of coronary artery disease: stable angina

S W Davies Department of Cardiology, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK