Hello there, whether you’re a patient, someone who knows a patient, or just looking to understand more about heart health, let’s discuss who is at high risk for Acute Coronary Syndrome.

Overview

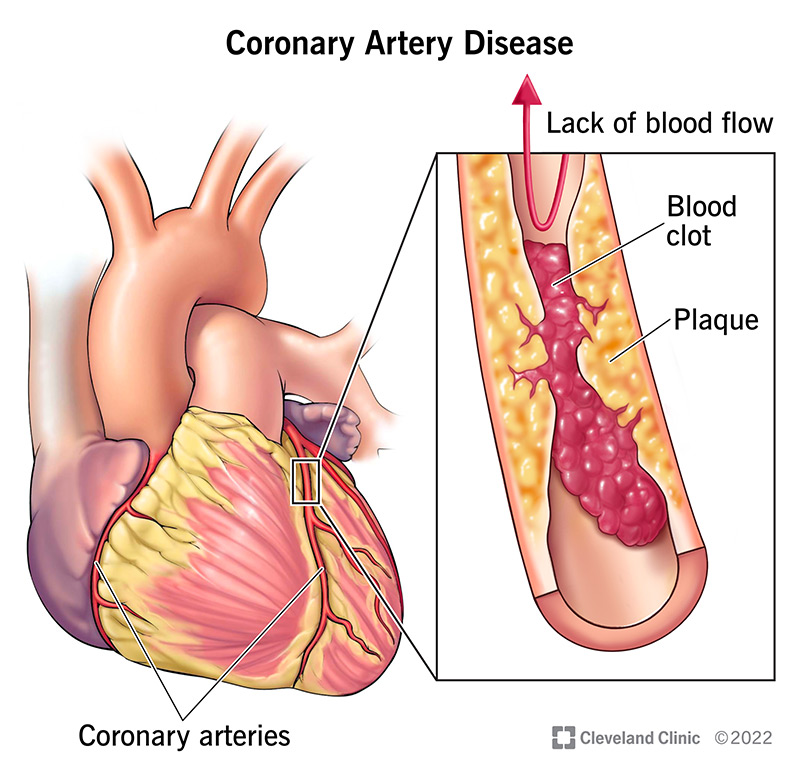

When someone experiences an Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS), like a heart attack, it’s typically caused by a blood clot forming in one of the heart’s arteries, blocking blood flow. This clot almost always happens because a fatty build-up in the artery wall, called an atherosclerotic plaque, becomes unstable and ruptures or erodes. Not all plaques are equally dangerous; some are particularly “rupture-prone” or “vulnerable.”

Our understanding of what makes someone high-risk for ACS has evolved. While we used to focus mainly on the individual “culprit” plaque that caused the event, we now recognize that it’s often a more widespread problem within the arteries, involving many potentially vulnerable plaques and general inflammation throughout the body. We also understand that the “fluid phase” of a person’s blood – meaning factors circulating in the blood itself – can make them more prone to clotting, creating what’s known as a “vulnerable patient”. So, high risk isn’t just about one bad spot; it’s about the overall health of the arteries and the body’s clotting tendencies.

In Details

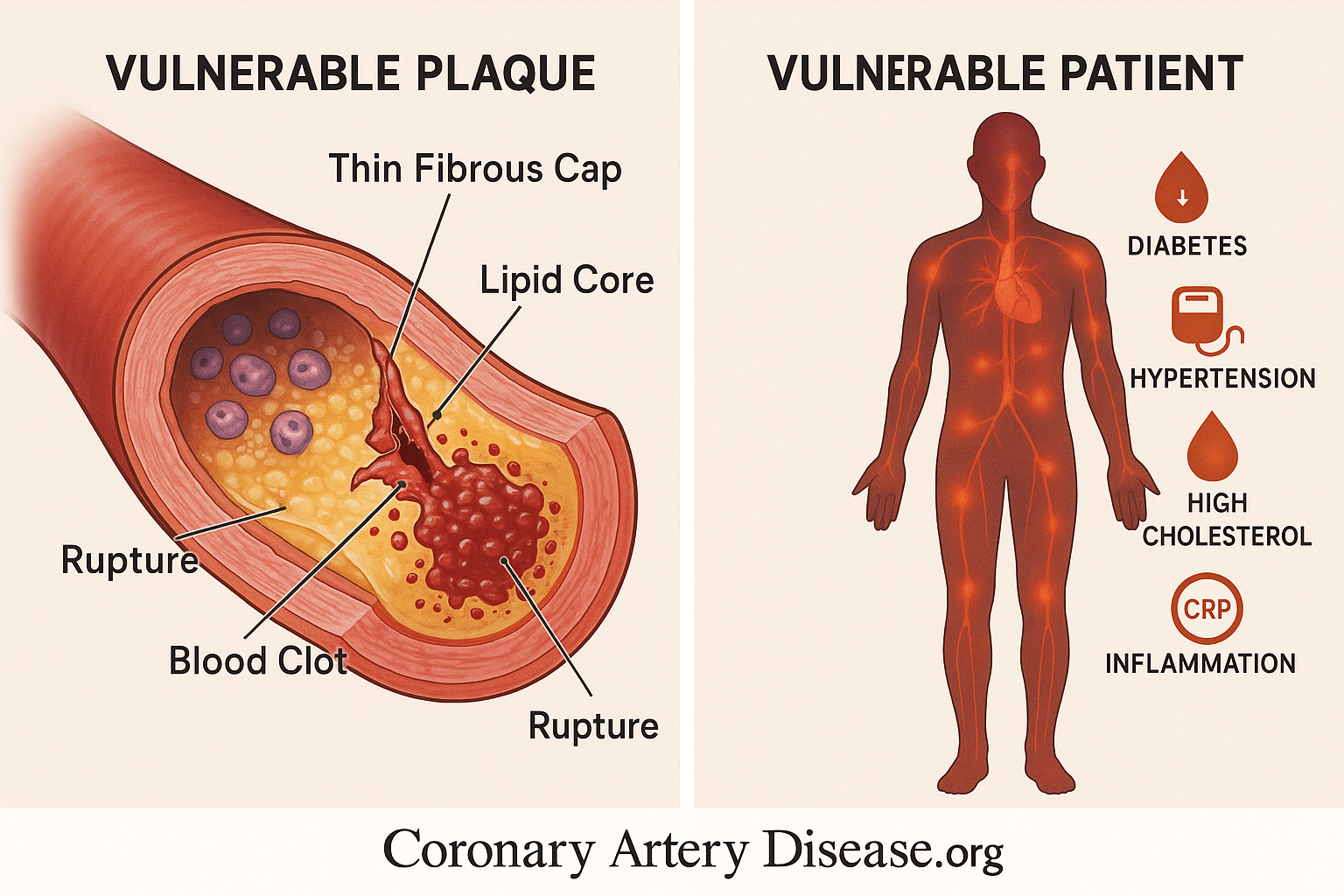

Let’s have a quick look at what characterize the vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques and patients

- Presence of atherosclerotic plaques with a thin, fragile fibrous cap.

- Plaques containing a large, soft lipid (fatty) core.

- Plaques with a high number of inflammatory cells (e.g., macrophages).

- Plaques with relatively fewer smooth muscle cells, which help strengthen the cap.

- Widespread inflammation throughout the coronary arteries, not just at one site.

- Circulating blood factors that promote clotting or hinder clot breakdown (e.g., high Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 or PAI-1).

- Presence of “hidden” plaques that have grown outward (compensatory enlargement) and don’t cause significant blockages but are still vulnerable.

- Conditions like diabetes and obesity which can increase pro-clotting factors.

A plaque that is “rupture-prone” or “vulnerable” possesses specific anatomical and cellular characteristics that make it susceptible to disruption. Primarily, these plaques are distinguished by a thin, fragile fibrous cap, which is the protective layer covering the fatty core. Beneath this cap lies a large, soft lipid core, rich in cholesterol and cellular debris. This core is particularly unstable. At a cellular level, these vulnerable plaques are heavily populated by inflammatory cells, such as macrophages, which contribute to weakening the fibrous cap by secreting enzymes that break down its structural components.

Conversely, they tend to have fewer smooth muscle cells, which are crucial for maintaining the cap’s strength and integrity. The death of lipid-laden macrophages within the plaque can also lead to the release of tissue factor (TF), a powerful trigger for blood clotting, into the extracellular space. While fibrous cap rupture is the most common cause of acute coronary thrombosis, other mechanisms like superficial erosion of the artery lining, bleeding within the plaque (intraplaque hemorrhage), or erosion of a calcified nodule can also trigger a clot.

The understanding of ACS has significantly shifted from viewing it as solely due to a single, critically narrowed artery or one “vulnerable plaque.” We now recognize that atherosclerosis is a widespread inflammatory disorder. Many plaques, even those that do not cause significant narrowing (known as “non stenotic lesions”), can be vulnerable. This is because arteries often undergo compensatory enlargement, meaning they grow outwards to accommodate the plaque without blocking blood flow, making the plaque “hidden” from detection by traditional angiography. Patients experiencing ACS often have multiple disrupted plaques throughout their coronary arteries, not just one “culprit lesion,” indicating a pan-coronary process driven by diffuse inflammation.

This widespread inflammation in the arteries, alongside the specific characteristics of individual plaques, contributes to the overall risk. Furthermore, systemic factors in the “fluid phase” of the blood also play a critical role. For instance, high levels of Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) can reduce the body’s natural ability to dissolve blood clots, predisposing an individual to thrombosis. Conditions like diabetes and obesity can elevate PAI-1 levels, further contributing to a pro-clotting state. This collective understanding has led to the concept of the “vulnerable patient,” where overall systemic factors, combined with multiple vulnerable plaques, define the true risk of ACS.

Other Similar Questions

Can a person have many vulnerable plaques?

Yes, studies show that patients with ACS often have multiple vulnerable plaques throughout their coronary arteries, not just one.

What is the “no-reflow phenomenon”?

This is when tiny pieces of a ruptured plaque or clot break off and travel downstream, blocking the very small blood vessels (microcirculation) in the heart muscle, even if the main artery has been opened.

What is the dual-phase approach to treating acute coronary syndromes (ACS)?

Beyond dealing with the immediate “culprit” lesion, the second phase focuses on “stabilizing” other plaques and reducing the patient’s overall vulnerability to future events. This means not just fixing the visible blockage, but also tackling the underlying, widespread issues like inflammation and the body’s tendency to form clots. This comprehensive strategy aims to protect against future acute events, which is crucial for long-term heart health.

Resources

For more detailed information, you can refer to the source document:

• Libby, P., & Theroux, P. (2005). Pathophysiology of Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation, 111(25), 3481–3488.