Hello there, whether you’re a patient, someone who knows a patient, or just looking to understand more about heart health, let’s discuss what causes a blood clot in Coronary Heart Disease.

Overview

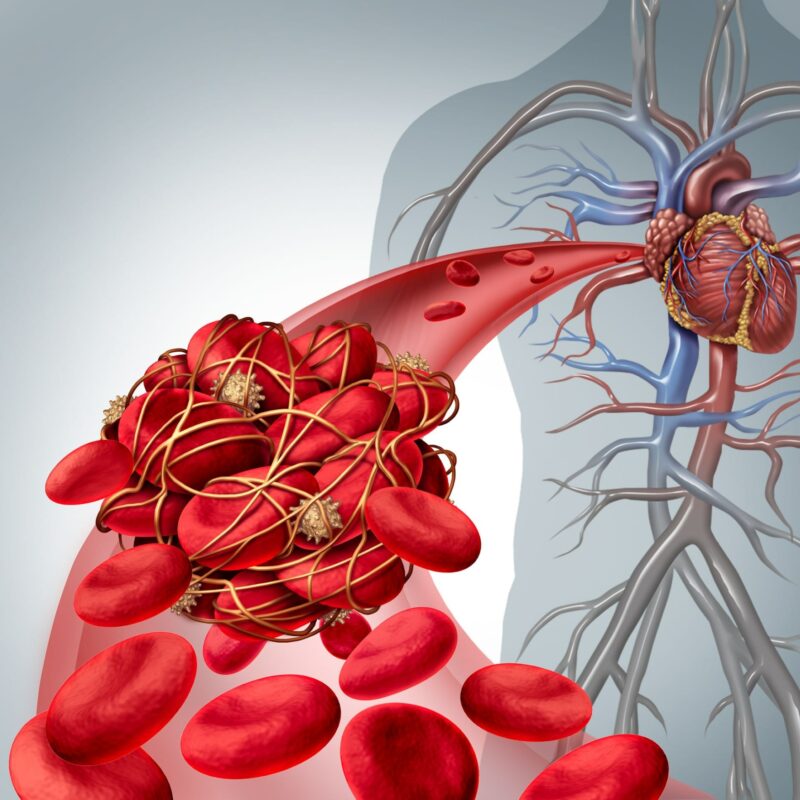

When we talk about serious events like a heart attack, a blood clot forming in one of the heart’s arteries (coronary arteries) is almost always the cause. This isn’t just a random event; it’s typically triggered by something happening within the artery wall itself: the disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque. Imagine the artery wall as having a delicate inner lining. When this lining, where a fatty plaque has built up, gets damaged or cracks, the material inside the plaque gets exposed to the blood flowing by.

This exposure acts like an emergency signal, causing blood cells called platelets to rush to the site and become sticky, and also activating the blood’s natural clotting system. This rapid response is normally meant to stop bleeding, but in the artery, it can quickly lead to the formation of a large blood clot that blocks the artery, cutting off blood flow to part of the heart muscle. This process involves a complex interplay between the “solid” components exposed from the plaque and the “fluid” components within your blood.

In Details

A condition called Acute coronary syndrome happens, and here we are about to know what triggers it and how does it strat with the formation of the clot.

Let’s have a quick look at what happens first

- Physical disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque (e.g., rupture of its fibrous cap, superficial erosion).

- Exposure of collagen from the plaque’s extracellular matrix to the blood.

- Activation and aggregation of platelets.

- Exposure of Tissue Factor (TF) from within the plaque.

- Activation of the coagulation cascade.

- Formation of a platelet-fibrin blood clot (thrombus).

- Influence of “fluid-phase” blood factors, such as high levels of Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1).

Acute coronary syndromes, such as heart attacks, are overwhelmingly caused by the physical disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque within a coronary artery. This disruption can take several forms, most commonly a tear or rupture in the plaque’s protective fibrous cap. Less frequently, it can be due to superficial erosion of the artery lining, bleeding within the plaque itself (intraplaque hemorrhage), or the erosion of a calcified nodule. When any of these disruptions occur, the inner contents of the plaque, which are highly reactive, are suddenly exposed to the flowing blood.

This exposure immediately triggers a cascade of events at a molecular and cellular level. First, contact with collagen from the exposed extracellular matrix of the plaque causes platelets to rapidly activate and stick to the site. Platelets are tiny blood cells crucial for blood clotting. Simultaneously, Tissue Factor (TF), a powerful pro-clotting protein produced by macrophages (a type of immune cell) and smooth muscle cells within the plaque, is also exposed.

This Tissue Factor initiates the coagulation cascade, a complex series of chemical reactions that leads to the formation of thrombin. Thrombin then plays a dual role: it not only further amplifies the activation of platelets but also converts a blood protein called fibrinogen into fibrin. The activated platelets also release von Willebrand factor. Together, fibrin and von Willebrand factor act as molecular “glue,” forming a dense, three-dimensional network that traps more platelets and other blood cells, quickly building up a “white” arterial thrombus (blood clot).

Beyond the direct “solid-state” triggers from the plaque itself, the “fluid phase” of your blood also plays a role in how likely a clot is to form and persist. For example, higher circulating levels of Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) can predispose you to clotting. PAI-1 reduces your body’s natural ability to break down clots, meaning any clot that forms is more likely to grow larger and last longer. Conditions like diabetes and obesity can increase PAI-1 levels, and hormones associated with high blood pressure can also boost its expression. This interplay between the “vulnerable plaque” and a “vulnerable patient” (due to blood factors) determines the risk of a cute coronary syndrome.

Other Similar Questions

What makes a plaque “vulnerable” to rupture?

Vulnerable plaques are typically characterized by a thin, fragile fibrous cap (the protective outer layer), a large, soft lipid (fatty) core, and many inflammatory cells while having fewer smooth muscle cells that help strengthen the cap.

Do only large blockages cause clots?

No, many dangerous blood clots form at sites of plaques that do not cause significant narrowing (non stenotic lesions). These “hidden” lesions can have large fatty cores and thin caps, making them prone to rupture and causing a heart attack even if they haven’t caused any symptoms or noticeable blockages beforehand.

Is it just one problem spot in the arteries?

Not necessarily. While an acute event might stem from one “culprit lesion,” research shows that patients with acute coronary syndromes often have multiple disrupted plaques throughout their coronary arteries, and the underlying inflammation is often widespread, not just limited to one area.

Resources

For more detailed information, you can refer to the source document:

• Libby, P., & Theroux, P. (2005). Pathophysiology of Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation, 111(25), 3481–3488.