Overview

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) is a serious condition affecting the heart’s arteries. It’s often misunderstood, but our scientific understanding has greatly evolved. Previously, it was thought to be simply a build-up of cholesterol, like a plumbing problem where pipes get clogged. However, we now know that CAD is primarily an inflammatory disorder. This means that inflammation—the body’s natural response to injury or infection—plays a central role in every stage of the disease, from the very beginning of plaque formation to the sudden, serious events like heart attacks.

CAD can show up in two main ways: as a long-term (chronic) condition, where symptoms might develop gradually, or as sudden, severe events (acute coronary syndromes like heart attacks or unstable angina). Importantly, these acute events often happen due to issues in blood vessels that weren’t even severely narrowed, challenging the old idea that only critically blocked arteries were dangerous. This new understanding means that treatment needs to go beyond just fixing blockages; it must also address the underlying inflammation and the overall health of your arteries.

In Details

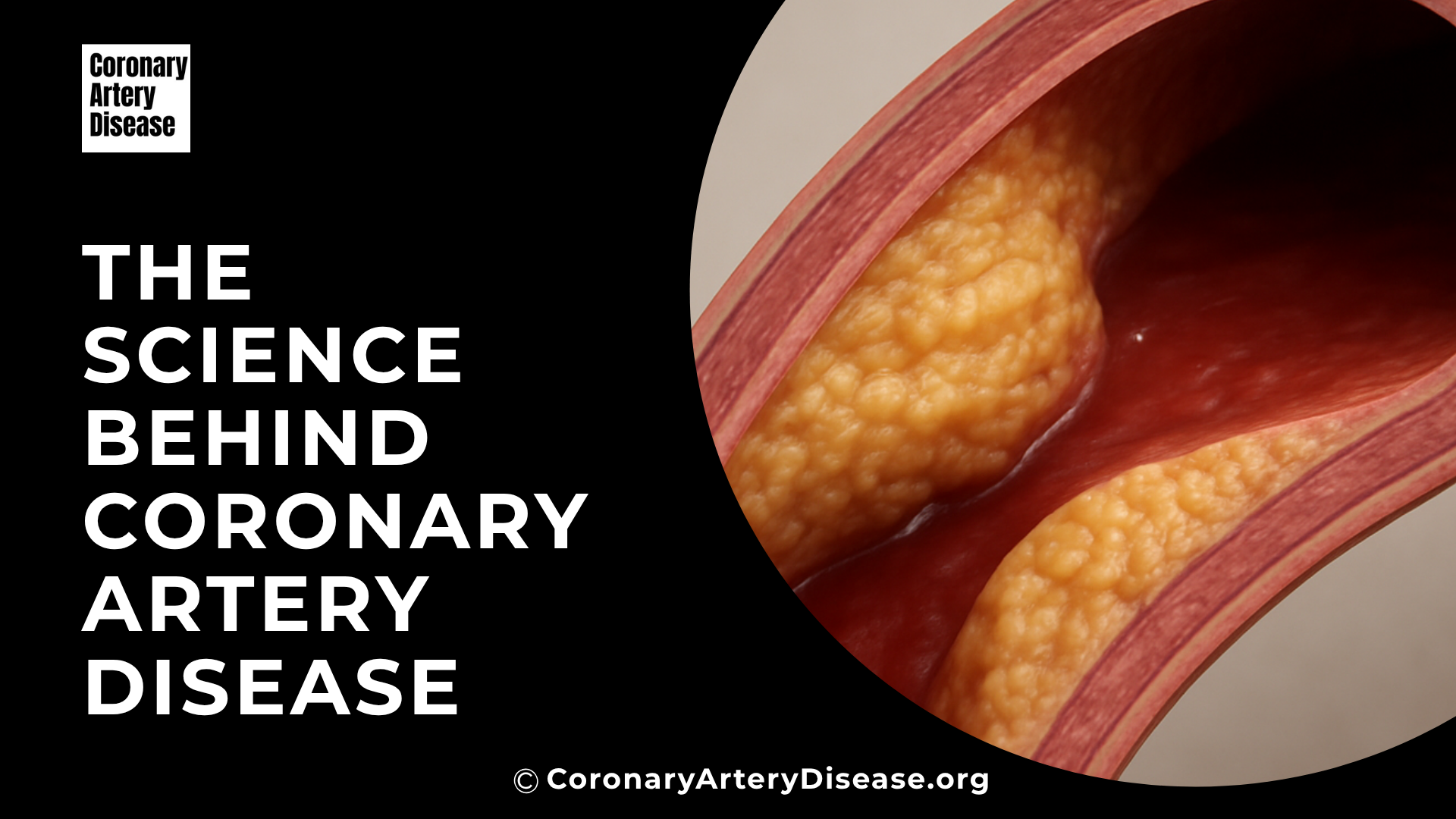

At the heart of CAD is a process called atherogenesis, which is the formation of fatty plaques within the artery walls. This process starts when the inner lining of your arteries, called the endothelium, encounters various “risk factors”. These can include things like high cholesterol (dyslipidemia), high blood pressure, high blood sugar from diabetes, or even inflammatory signals from excess body fat. In response, the artery lining starts to express special “sticky” molecules that attract certain white blood cells, primarily immune cells called monocytes and T lymphocytes, from your blood. These cells then stick to the artery wall and move into the deeper layers. Once inside, these immune cells, along with the artery’s own cells, begin to communicate through inflammatory signals, setting the stage for plaque development.

As this inflammatory process continues, muscle cells from the artery wall migrate into the inner lining and start to multiply. They also produce a complex mesh of proteins and other substances that form the main structure of the plaque. Certain parts of this mesh can trap cholesterol particles, making them more vulnerable to damage and further fueling the inflammatory response. Over time, calcium can also build up, making the plaque harder. As the plaque grows, fat-laden immune cells can die, releasing substances like tissue factor, which is crucial for blood clotting. All this accumulated fat and debris creates a soft, fatty core within the plaque, often called the “necrotic core”.

One key insight is that for much of its life, an atherosclerotic plaque grows outwards, away from the centre of the artery. This is known as “compensatory enlargement”. This outward growth means that a significant amount of plaque can exist without narrowing the artery’s opening (the lumen). So, even if your angiogram (an X-ray of your blood vessels) looks relatively clear, you could still have widespread plaque build-up. These “hidden” lesions, which often have a thin protective outer layer (fibrous cap) and a large fatty core, might not cause any symptoms until they suddenly rupture and trigger a blood clot.

Most acute coronary syndromes, like heart attacks, are caused by a sudden event: the disruption of one of these plaques, leading to the formation of a blood clot (thrombosis) that blocks blood flow. The most common way this happens is when the thin, protective fibrous cap over the plaque ruptures completely. Less commonly, the surface of the plaque might erode, or bleeding might occur within the plaque itself. When a plaque disrupts, it exposes materials like collagen and tissue factor (TF) inside the artery. These substances are powerful triggers for platelets (tiny blood cells involved in clotting) and the body’s clotting cascade, quickly forming a thrombus (blood clot) that can block the artery. Beyond the plaque itself, factors in your blood, such as substances that prevent clot breakdown (like PAI-1, which can be elevated in conditions like diabetes or obesity), can also increase your risk of dangerous blood clots.

Comparisons

Our understanding of CAD has shifted significantly:

- From Cholesterol Storage to Inflammation: CAD was once primarily seen as a disease where cholesterol simply accumulated in artery walls. Now, it’s understood as an inflammatory disorder at its core, with inflammation driving plaque formation and progression.

- From Narrowing to Widespread Disease: Doctors used to focus heavily on how much the arteries were narrowed (stenosis), which was easily seen on angiograms. However, we now know that such narrowings are often just the “tip of the iceberg”. Most plaques don’t cause significant narrowing due to “compensatory enlargement” (outward growth). This means CAD is often a widespread disease affecting many arteries, not just a few isolated spots.

- From “Vulnerable Plaque” to “Vulnerable Patient”: Initially, there was a search for a single “vulnerable plaque” that was prone to rupture. While certain plaque characteristics (thin cap, large fatty core) do make them risky, we now recognise that patients prone to acute events often have multiple such plaques and widespread inflammation throughout their arterial system. This shift emphasizes that the “vulnerable patient” (someone with overall risk factors and diffuse arterial inflammation) is as important as, if not more important than, identifying just one problematic plaque.

- From Symptom Relief to Plaque Stabilisation: Traditional treatment for chronic CAD focused on relieving symptoms by improving blood flow, often through procedures like angioplasty or bypass surgery. While these are still vital, the modern approach also prioritises “stabilising” other plaques and reducing overall cardiovascular risk, not just treating the most obvious blockages. This involves aggressive management of risk factors and systemic therapies that combat inflammation.

Other Similar Questions

- How is CAD managed or treated now? Current management involves not only procedures like angioplasty or bypass surgery to open severely blocked arteries but also crucial long-term strategies. These include aggressive management of modifiable risk factors (like blood pressure, cholesterol, and diabetes) through lifestyle changes and medications (such as statins, aspirin, and ACE inhibitors). The goal is to rapidly stabilise plaques and reduce overall inflammation to prevent future acute events.

- Can CAD be prevented or reversed? Lifestyle measures, such as a healthy diet, regular exercise, and not smoking, are the foundation for preventing CAD. Aggressive management of risk factors has been shown to slow disease progression and can even lead to some regression of atherosclerosis. While plaques might not always shrink visibly on angiograms, studies suggest that they can become more stable and less prone to rupture, which is a key aspect of “reversibility”.

- What are biomarkers, and how do they relate to CAD? Biomarkers are measurable substances in the blood that can indicate disease activity. In CAD, certain inflammatory markers, like C-reactive protein, can predict the risk of future heart events. Research is ongoing to see if monitoring these markers can help guide treatment, especially given that some medications, like statins, have anti-inflammatory effects independent of their cholesterol-lowering actions.

Resources

The information provided in this summary is based on the following scientific article:

- Libby, P., & Theroux, P. (2005). Pathophysiology of Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation, 111(24), 3481–3488.

This article provides a comprehensive review of the evolution in understanding the mechanisms of coronary artery disease. It is a valuable resource for deeper scientific understanding.

Leave a Reply